Eight cows graze in a painting on my wall. A stuffed cow sits in my bed. In a picture frame, eleven cows line up, silhouetted to a Nebraska sunset. Four cows, in ornament form, hang from a little white Christmas tree. And on a postcard resting on my shelf stands one cow, drawn, in black and white, by a special freckled girl. The cow in this drawing stands behind a wooden picket fence with its body and head attuned to whoever is beyond. Its black spots transcend into the sky with puffy scalloped clouds. Two years ago I had no cows. I drank almond milk and ate no red meat.

Dotted across Lancaster county like poppy seeds on a bagel, Cows are munching, mooing, multiplying, milked two times a day, living a pastured life obscure from my own. It was on a bikepacking trip across Vermont where this curiosity seeded — eating a granola bar across a steel wire from a Jersey, a Guernsey, and a black cow, where their eyes laid on me with an unsearchable depth, black marbles an inch in diameter, that when focused on you, convinced you the entire world and all its emotion could fit inside.

I’m not in love with cows. But once I watched a sunset over the plains of Nebraska as a herd galloped towards me from afar. They lined up like dominos, wagging their tails, focused on me, for a time that I can’t report in any other way but extraordinary.

There are over 1,800 dairy farms in Lancaster County, many of them Amish, owning under a hundred head, up to a few farms with over fifteen hundred head, making the county sixth in the nation for dairy production. If I was going to embark on an exploration to see cows in plenty I suppose there are only five other counties offering more. But this was my backyard. So on a cool sunny morning in March of 2023 with a week off between changing jobs, I looked at my red gravel bike slanted against the garage door like a ship in harbor, loaded with packed nylon bags, a tent, and a sleeping bag. In the handlebar bag I crammed a 3×5 notebook and a Sony camera, fully charged, poking out slightly, ready to record the events that would ultimately become — The Cow Story.

MARCH 20TH, 2023

I’m riding south from the village of Colebrook, over the wooded ridge, and descending across the county line, into Lancaster. The bike below me is equipped for three days of riding and two nights of camping. My goal is simple: Learn about cows through all means. A mile later I stop along a bend in the road where the barn is so close the cows can almost hang their noses over the white line. There’s no one around but a school of Holsteins (the black and white ones), swaying my way, each of them in a twelve hundred pound trance. I grab my notebook:

“Colebrook rd. cows are docile, move slowly towards you,” I scribble, “pee like a fire hose – wherever they want.”

Now there was a place I used to pass daily as a bus riding youth, a non-descript building, and I recall it had something to do with dairy. So I wind through Rapho township, stop to photograph some cattle, exchange waves with an Amish boy riding a tricycle, and at last prop my bike against that very building. Inside I meet April at the reception desk. I stand wearing a black helmet, a sky blue windbreaker, black cycling bibs, forest green quarter length socks, and gray shoes with a cyan mismatched shoelace, sniffing up the runny remnants of the cold morning.

“I’m on a — sort of a quest…” I say, breaking a smile, “This week I’m a student of the cows…”

April is the business manager at the Lancaster Dairy Herd Improvement Association (DHIA). While confused she is still receptive and friendly. And she informs me of the operation, pointing out the gray office area filled with cubicles under fluorescent lights and then over to a window into a room with white lab coated ladies swishing samples and pushing buttons. There’s around twenty employees working between the office and lab, and over one-hundred field technicians record data at dairy farms across Lancaster county and beyond.

The DHIA works closely with dairy farmers by testing essentially everything going in and out of a cow, all in the name of improving the herd. The herd health, April tells me, among other factors, is dependent on the efforts given to cleanliness and care. The DHIA helps farmers by supplying a framework of metrics to improve their herd, from testing forage(grass or hay the cows eat), pregnancy health, water quality, and even the soil composition the crops are grown in. These factors optimized by farmers result in happier cows producing higher quality milk, and more of it. Aside from government required testing, farmers are not required to test anything or send their milk to DHIA, but there’s no better way to determine the milk quality, measured partly in butterfat content, and track indicators that lead to it. Higher quality milk means higher prices to farmers.

“So cows are just like us.” I say, pointing at the glass candy bowl on April’s counter” If all I did was eat from this candy jar I wouldn’t be that fast on my bike. Likewise with cows, what they eat affects what they produce”

April nods.

This certainly isn’t novel; they say what you eat is what you are, but it’s beginning to reveal that the cows buttoned across the landscape are more than just cows. They are complex, like us, and have a team of consultants monitoring every corner of their health.

“Thank you,” I tell April, thinking it’s now my time to go, “Can I take a piece of candy?”

The cherry lifesaver is gone before I roll through Manheim, home of the Manheim farm show, where I once volunteered at the milkshake stand, numbing my fingers filling styrofoam cups with Kreider’s dairy ice cream.

As of 2018, Kreider’s dairy farm is the largest in the county, housing over 3,700 cattle. It was during an elementary school field trip I last visited Kreiders. We rode a trolley around the expansive grounds listening to a tour guide.The trolley still runs today but now they’ve added a 100’ tall silo, with a spiraling staircase allowing tourists to overlook the farmlands which ultimately feed the cows.

I park my bike next to the yellow “Snapchat Zone” sign by the silo along with other dairy tour signage. I never made a reservation for a tour and there’s no one to ask. But the door to the building is open. Inside I click-clack my cycling shoes on the tile floors, pausing for the Kreider family history displayed on the walls. Still, no one is around. A glass door looks interesting at the end of the hallway so I click clack, click clack, and peering through the glass I see cows spinning. With efficiency and extravagance, over a hundred Holsteins, on a stainless steel merry-go-round are milked in centrifugal fashion. They must have added this since I was here. I give a head nod and a smile to a worker supervising the ride but he’s busy working. Click clack. Click clack. Back along the hall and behind another glass door a few workers are stationary, having their lunch. This time I open the door. “Do you guys milk the cows?”. I ask. They were nice, but only gave awkward smiles and slightly raised eyebrows.

A 2017 Texas A&M study found that over 50% of the nation’s dairy workforce is foreign born. According to Carol Hardbarger of the PA Milk Marketing Board and her 2019 survey, most dairy processors report trouble finding workers. Immigrants fill that need, producing quality milk for consumers while injecting money ($24.6 Billion in 2018) back into the Economy. There’s a good chance the milk you drink or the butter you spread, was in part, processed by immigrant hands.

I leave the parlor wondering how no one questioned me yet, so I push my luck to find some cows in the feeding house. Hundreds of them with numbered ear tags line either side of a bay as long as a football field. Large fans blow above. I see #7315. She’s munching on forage and her eyes reflect a certain peacefulness. Although she is more than just a number, a second glance reveals – she’s Mallary. The pretty girl had the best view out the barn and across the road to the vibrant light green fields of spring. Next was Clarissa, and beside her, Ensyn. Across the hallway, equally satisfied, stood Efferhild, and Dibs.

The backroads of Lancaster county bend and meander, wrapping around farms, lining creek valleys, and climbing up forest lined meadows, lacing together a bucolic scene. Riding a bicycle here is nearly perfect. Across any direction you see dozens of silos sprouting from the horizon like blue and gray buoys in rolling waves.

I head eastward, pedaling past Brickerville and nearing Hope, passing one of those black lettered changeable signs from an Amish or Mennonite farm: “IF IN DOUBT, DO NOT DO IT.” It says. It’s good advice for the overzealous, but reinforces the timid. Or maybe the sign was a lesson to all, after the farmer’s young son disregarded his own doubts about using a bed sheet to parachute off the barn rafters.

I have plenty of doubts. In starting this trip I had dreamed about milking cows and sleeping in pastures and interviewing dairymen across the county. Yet for some reason it felt so criminal to be curious, to bother working men and women, them in jeans and flannels and me, in spandex, on an ordinary Tuesday morning. If we only acted without doubt I say we wouldn’t do much at all. So I am still looking for a dairyman and milking a cow wouldn’t hurt.

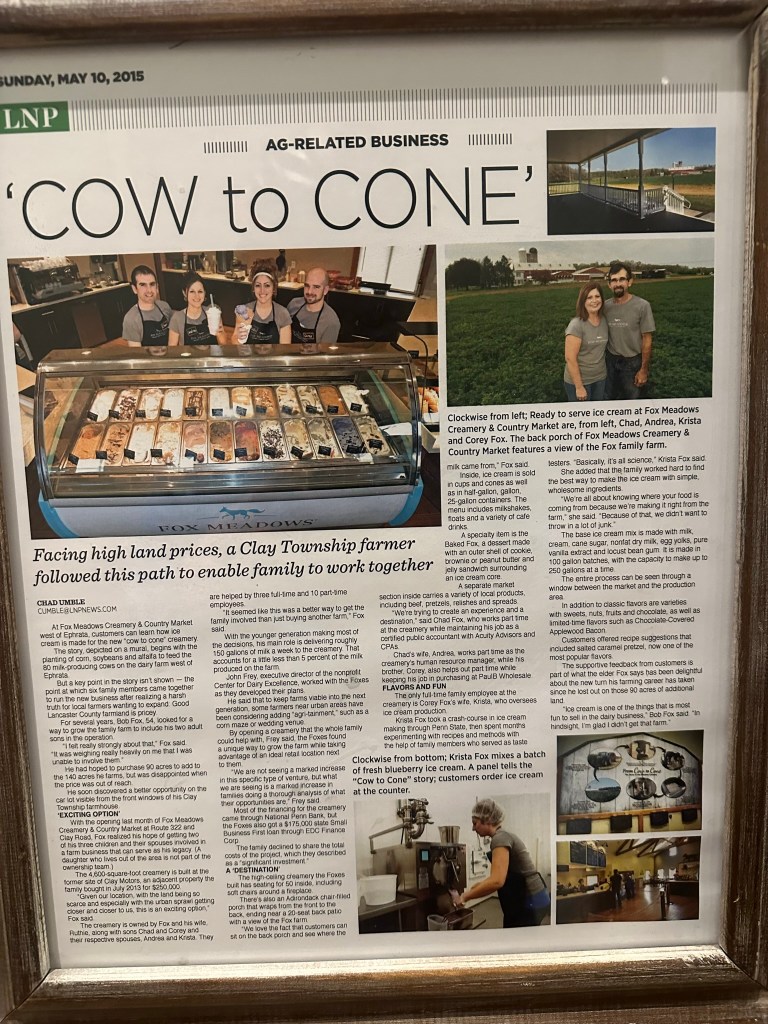

The girl behind the register at Fox Meadows Creamery says she has never been to the 80 cow farm next door, which supplies all of the ice cream for the facility. Once a year the owners give an employee tour, but she was out of town that day. There are cow prints and cutouts on the walls varied with several cow facts, like how calves can walk only an hour after birth. I sit down to eat a sandwich staring out the window through the covered porch, across a field and to the farm beyond. Everything truly revolves around the cow. People work the fields to feed the cows to produce the milk to make the ice cream to serve the people who will on any given Friday night wait in an hour line just to eat it. After finishing up I ride out by the Fox Meadows farm to see if I can talk to anyone. Even rode by twice, but no luck.

Across the street from Fox Meadows I meet an elderly mennonite lady at Clay bookstore.

“What do you know about cows?” I ask. Her response is quiet and unintelligible but she motions to follow her. The whole place is packed with mennonite and amish women and it’s dead silent except for my cycling shoes sounding like high heels. She takes me to two sections. In one, I find an academic book: “Calf” by a man with a Ph.d. I flip to a graph where I learn that a 220lb calf can grow 2.5lbs per day off 2,500 calories. The second is the independent farming section, where I suppose the smallest of farmers will go if they desire off-grid living: “Ten Acres Enough – The Classic 1864 Guide to Independent Farming”, or, if I’m more pressed for space, “Five Acres and Independence”. If you have more desire than land, M.G. Kains’ “We Wanted a Farm” is for you. Next to those, and my purchase for the day: Grass-Based Dairy Farming.

THERE ARE TWO THINGS TO DAIRY FARMING

North of the hillside town of Ephrata is a widespread valley of farmland before hitting the turnpike and the wooded furnace hills beyond. It’s early afternoon and my new book hangs out of my front bag like a small sail, helping me east through the valley farmlands in hopes of finding a dairyman. I see some Belted Galloways grazing along a distant hillside, one of my favorite cows, a Scottish breed sometimes referred to as Oreo cows due to their white midsection belt with black ends.

I pedal more, once speeding up to avoid a sprayer’s manure cloud carried by a westerly wind, before finally resting my attention on a white canvas hoop barn illuminated by the quiet afternoon sun. Several furry calves stand in the barn’s large opening looking out towards me while wagging their tails and stumbling across each other with their pointed bones protruding out of their undeveloped hulls. That’s a nice farm. I turn my bike around to see who’s around.

The only person I find is the neighbor, a pleasant man happy to talk and hear of my mission. He tells me the dairy farmer’s name is Paul; who is friendly in nature. “Think I could just ride in there and look for him?” I ask.

“Yeah, he’s a great guy!”

When I approach Paul he is talking on the phone so I stop about ten paces away and smile. Paul has dark hair, a short gray beard, and round glasses. He wears a flannel with jeans and both are dirty. The phone call is brief.

“Hello!” I yell, rushing to introduce myself, “I’m on a bit of a quest trying to learn as much as I can about cows… Do you mind telling me about your farm?”

“Oh yeah, sure thing!”

“I saw your calves along the road and thought your farm was nice, and wanted to talk to you.” And with that Paul is off. I asked for 20 minutes of his time but I soon realize he could talk all day. This is his craft.

“Success in dairy farming comes down to two things…” Paul summarizes, “Feed — and cow comfort”

We walk across the sunny cracked pavement and into a white cinder block room off the side of the milkhouse — the milk room, I’ll call it. There are pipes and plastic tubes along the walls connected to the colossal shiny tank bridging through the wall. The tank never fills completely, Paul shares, as it’s pumped out every other day by the “Maryland and Virginia co-op.” Cooperatives are like unions for the dairy industry. Members of the co-op, usually small farmers, save costs by pooling their resources in order to market their milk and negotiate prices, and even share in profits. Paul grabs a clipboard off the wall recording visits from the milk truck. 17,000lbs of milk was taken yesterday.

Across the wall is the milking parlor. It is by no means pretty, or spinning, yet it is the only place I want to be at the moment. A good portion of Paul’s 130 cows line the long building in two rows, eating forage, drinking warm water (how they like it), or lying down for a break. To milk the cows Paul uses four tentacle-like suction cups that are lubricated with a sanitizer to protect the cows from infection. “It works best when they are stimulated” Paul says, feeling the large mass under their hind legs.

“So, a bit of anatomy here… what is that?”

“The udder.”

“Oh, yeah yeah” Of course.

The udder hangs underneath the cow and for a high producing holstein it can hold up to 80 lbs. Not all of Paul’s cows are being milked at the moment but at 17,000lbs every other day over 130 cows that is 65 lbs of milk produced per cow, per day.

Next in our tour is the calf barn that initially drew me in. Outside the barn calves poke out of their little white igloos and inside are a half dozen calves in a ventilated pen. They are black and white holsteins, tall and skinny, with large leaf-like ears, soft, pure hair, and look clumsy as they walk. The curved ceiling is illuminated to an ethereal glow and the window portrait of the sprawling countryside emits a hopeful aura. A black calf trots over to me and I scratch her velvet forehead. The calves are Paul’s favorite aspect of the farm. He keeps their pens especially clean and often tends to them. “This is the start right here – a lot can be gained here” Paul adds, “The growth rate is amazing. If you get them going fast as calves it follows them through for life.”

Paul has recently invested in an automatic milking system. It sits in the room next to the nursery, mixing formula and piping it directly into the pens. “We used to feed by hand. About 3 times per day was all we could do. Now they are getting fed four times a day.” White ear tags register with the dispensing nozzle in the pen to record which calf is drinking and how much. Paul then shows me a digital screen displaying miniature animated cows with colors indicating the status of the calves’ drinking. “Looks like this one here is red,” Paul says, pointing to calf #441 on the screen. “She isn’t drinking much.

“So you’re concerned?” I ask.

“If she were 10 days old I would be, but she’s 68 so we can just monitor her closely”

Calf raising is arguably the most delicate and critical process on the farm. “You can’t mess around with calves.” Paul says. He checks on them twice per day, cleans their pens, and adds hydrated lime to their milk to prevent disease, which is the greatest threat to a high performing cow.

Up until now it’s clear that dairy farmers love high performing cows. And well fed, comfortable cows are outperforming poorly fed and miserable cows. “So what’s the ideal life of a cow?” I ask Paul, “like if a cow were an ideal baseball player. They are trained as kids in little league and private clubs and climb from there: High school, college – to the MLB, they play some good years then retire, start businesses, sponsorship deals — they’re killing it. So what does that look like for a great cow?”

“So what we really want” Paul begins “Well — we are feeding them milk, and then they switch to forage: hay, and there’s some grain in there. We want them to be converting feed to either meat or milk. Their stomachs are different from ours.” Paul is referring to a ruminant stomach of four distinct compartments, the largest being the Rumen. “The rumen is almost like — you ever hear of the term composting?” The Rumen is a fermentation vat where forage is broken down by microbes to create volatile fatty acids (VFA’s) — energy for the cow. The cows ruminate on the feed by rechewing the contents within the Rumen, known as chewing cud, to break it down further into VFA’s. I’m perhaps oversimplifying it, but the other three compartments approach a similar method to our stomachs by digesting with acids and enzymes. Any disease calves acquire will ultimately affect their stomachs — the cornerstone of their performance and comfortability. “If they are ill here,” Paul says, “they will have digestive issues that will affect them for life.”

From cow to cow, milk production varies dramatically, from four gallons per day up to twenty, with record breaking cows approaching twenty-five. Much like a baseball team, high performance players are kept and less performing ones are traded. Low performing cows are sold for meat.

Once a calf is 13 to 15 months old they are likely past puberty and have reached 55-65% of their mature body weight, which signifies the heifer is ready to breed. Once a heifer gives birth it becomes a cow. Next to the nursery, Paul takes me through a door to where the room expands into a large pen with several mature cows, who are either in the breeding process or already pregnant. There is no bull in the room. “Bulls can be a little aggressive,” Paul says, “You have to watch them. They can push you around a little bit.” Artificial insemination removes this hassle. “We can buy the semen of high end bulls with good genetics, a bull you could spend $20,000 on, even $50,000 — for one bull.” Paul says, “But we can just buy units of semen for twenty, twenty-five bucks.”

A few of the cows have orange chalk spread across their behinds. I had seen the same thing near Fox meadows, so I ask about it. On cows Paul intends to breed he applies a coat of chalk to their behind. Then, he waits. “The one that is in heat will get it all rubbed off” Paul says. Other cows will sense which cow is in heat and mount them, thus rubbing off the chalk. “I don’t know what motivates them to do that, but they’ll do that.” Paul elaborates that the process is not a science, “but it works in general.”

Paul is a third generation dairy farmer. He moved to this current farm in second grade, from down the road a bit. He has two brothers, also dairymen, with their own farms in Lebanon and Cumberland, who sometimes help with harvesting. Between his sons and a few part time employees Paul can run the entire operation. Paul regards dairy farming as an art as there are plenty of ways to manage every aspect of the farm but he’s equally interested in the economics of dairy. The cow is the vessel and all success must flow through them; the resources in, and resources out — all matter.

“To make a living on milking cows is about putting good feed into the cow, and taking good care of the cow. So we are constantly looking for ways to do it better – you know — where are our weak spots? We can always find places where we can improve but we don’t have all the time and money to do it all at once.”

It’s often the mundane daily chores that get in the way of higher level strategizing. And Paul is not afraid of technology to do this, from his latest investment in the automatic milking system to his dreams to one day have a robotic milking system which allows the cows to come and go whenever they want to be milked. To me, that speaks of cow comfort. For Paul: “If I can reduce daily chores, I can tend to the calves… I can look at farming better crops that will go back to the cows.” Paul is constantly improving his strategy by keeping up on dairy prices, attending conferences and seminars, and reading the latest industry insights.

At this point we only have a few barns left. There’s one we pass with the barn doors spread open and hay bales piling up two stories. I watch Paul’s mini goldendoodle dart through the doors and up to the top of the bales in mere seconds. “That’s Snickerdoodle” Paul tells me. The barn across from the hay is filled with large dusty equipment that goes about mixing feed. Metal switches with white labels allow Paul to make recipes his nutritionist recommends based on the current cow’s milk production. “It’s basically the order screens at Sheetz.” I say. This gets a small chuckle from Paul, “Yeah I guess you’re right”

In the last barn, the largest of them all, are all the machinery: the chopper, the spreader, the sprayer, and other wheeled machinery used to farm the over 300 acres their family owns. For the few harvesting processes Paul can’t do, he contracts it out. Outside the barn Paul’s sons and various truck parts are sprawled across the cracked pavement around an old white pickup. Even though months away, they are preparing for harvest time, where everything must be working perfectly. I ask about this preparation and Paul reassures me that on the farm there is never enough planning and preparation. “We’ve invested in the land. We’ve invested in the equipment. We’ve invested in the cattle. We’ve invested all this time and money — Of course we’re going to do everything we possibly can do to be successful.”

I feel Snickerdoodle circle around my ankles. She then jumps up on my thigh leaving a mud stain. Although, it feels like a mark of approval so I’m not bothered. I shake Paul’s hand and thank him before picking up my bike off the ground to ride away. It had been almost 2 hours on the farm.

THE BULL WITH TWO NAMES

Suppose I call it a day, now, pedaling my bike down a tattered country road South of Paul’s, on the outskirts of Lititz, Pennsylvania —I’d be more than satisfied. I only asked for 20 minutes of Paul’s time and he gave me the whole farm! I’m at sixty miles for the day and the sun is now casting long shadows — my wheels stretching oblong and my body reaching pole-like off the road and into the field. The warm spring air has everyone outside, on bikes and on walks and planning for this year’s landscaping. It’s also a Tuesday night, which means, “C4”, a young adult gathering at Calvary church in Lancaster. In January I met a sweet girl there and a few days ago we had our first date, lasting 7 hours before the hostess kicked us out. For tonight I made sure I packed a decent change of clothes in my frame bag. I need to see what she meant by saying she had a gift for me. It may strike her as odd me arriving on a bike. I certainly hadn’t told her of my plans to research cows and sleep in fields. But given how well the first date went, I want to say she would get on board, or at least tolerate my behavior. Regardless, I found my dairyman, and I’m feeling alive!

My legs are running off excitement but are nearly followed by hunger. But I think I can survive until a gas station. There’s one by the church. Looking to the left into the field I notice a young black steer galloping along, matching my pace, 20 yards away. He’s running along with his young bones draped by a sunlit black fur coat, over a field lined with the sproutings of corn, which surprisingly is not the chewed away meadow I’m accustomed to seeing. I’m new to this but normally you don’t mix corn with cattle. Then, I see why — there’s no fence between us.

“JOSH, OPEN THE GATE!!” I hear a man yell,

“ GIRLS, GO TO THE ROAD!!”

The steer is puffing and snorting and his eyes are darting around before locking onto mine and then bolting away from me and the road.

“Do you need help!?” I yell.

“Yeah!” the man yells back.

I swing off the road, toss my bike in the grass, and bolt into the field after the steer, who’s running inland.

The boy wrestles with the black steel gate to the steer’s pen as his father corrals the steer from further inland. The man’s young girls and I hold the line between the steer and the road, and we’re slowly able to funnel the wild, huffing and kicking steer towards the gate.

“JOSH OPEN THE GATE!!” The man yells as the beast is closing in

“I can’t!!” The boy yelps.

I wince as the steer approaches the boy. It stops 10 yards from the gate but then departs toward the house, threading between the shed and the garden and making a half-ton shot for the road. I pivot and start sprinting to intercept his path as I hear a metal clank. “I got it!” the boy yells.

The steer and I are narrowing in on each other and I’m starting to get the idea he doesn’t care so I back off, letting him continue towards the road. I have a helmet on but I still think being trampled would be rough. So the steer sprints toward the road on his own volition. All five of us stand helpless. He makes it halfway past the house where he halts, and whips his body back towards us. We can only watch as he weaves his way through the yard and past the girls and gallops through the open gate at once, into his pasture.

In a moment we convene at the gate — the dad, his three kids, and me, a stranger in spandex — laboring to find breath again. The man’s chest broadens and falls as he stares into the grass.

“What’s your name?” I ask.

“Andy — Andy Rutt”

Andy is a man in his thirties with an honest complexion. He smiles as I approach to shake his hand,“Thank you so much,” he says, “I’m sorry to interrupt your bike ride…”

“No, no” I chuckle, “you don’t even know…” I raise my hands to explain, “I’m on a bikepacking trip around Lancaster county. I like to write and I’m focusing solely on cows – cattle, and the dairy industry – wherever my bike takes me. I plan to write an article when I get back”

“Well you can put that in the article!”

I look over his shoulder to the steer, now calmly grazing in the pasture.

“What’s his name?”

“Girls?,” Andy asks, “ what do you call him?”

“Buddy…” the one girl mouths, then shoots a look at her sister, “but she wants to call him Ferdinand.”

CHURCH

Grace, the girl from the 7 hour date, had crocheted me a palm size succulent plant, of yarn, set in a brown crocheted pot. At five past ten we finally stepped outside of the church. She knew I biked there but little more. “My bike’s over here” I pointed along the church. As we walked I described my trip and luckily she looked beyond the initial shock factor.

At my bike, withholding no splendor in presentation, she revealed the soft crocheted plant. I accepted it, of course, but paused for too long looking for where to put it.

“Do you not want it?” She questioned.

“No, no! I’m just wondering where to put it.”

“Well,” she says, crossing her legs, “It looks like I’ll have to keep it until you take me on a second date.”

And thus the date was confirmed within minutes, at Fox Meadows, Saturday, around 6. The night was cool and by then most people had left the church.

“I will be heading to the south end of the county and returning along the river on Thursday… maybe I’ll roll by your place and I can say hello…” I continued to flirt.

“That sounds like an interesting proposition… but how are you going to find my house?”

“Well I’d need a hint, or something.” I probed.

She then asked for my phone and twenty seconds later handed it back with an address typed in maps. Before I could look up from the phone she was walking away. “Let me know!” She chimed over her shoulder with a sweet smile, her right foot kicking up — a Converse laced stamp to the interaction.

That little kick and smile was about the only warmth I could draw from within my gray one-person tent in the corner of a field Southeast of Lititz. A dog barked for three hours and something rustled the nearby brush, guaranteeing my alertness for hours more. The only reporting on cows was done at midnight. She went “Mooooooooo.”

LAND OF THE MOST BASIC OCCUPATION

In 2008, fifteen Ohio Amish farmers wrote “Grass-Based Dairy Farming ”, the book sold to me yesterday. The 46-page manual is for “young people who have marginal interest in farming.” My interest in the book is at least marginal, sitting at Coffee Co. Cafe in Lititz with it open in front of me, but I also only slept for a few hours so I mostly sit, sip warm coffee, and wait for my breakfast burrito.

Once satisfied, I pedal south. The back of the book sticks halfway out of my front bag; “The Concept” is revealed:

We, in the spirit of good land stewardship,are managers of the primary plant of God’s creation — grass. We harvest this grass in the most ecologically correct manner we can by our cooperation with the laws of nature and dictates of the bovine species. We then sell her milk as a reward for our stewardship and gain the satisfaction of providing for our families and our communities in a manner that violates neither the earth nor those that tread upon it.

April from the DHIA said that most Amish farmers are in the southern part of the county, and that’s where I’m heading. Beyond that, decisions at intersections are based on feeling and interest. “Raw milk” signs, or attractive sights of a faraway farm are enough to make the call.

The morning is warm enough that I only need my light blue windbreaker over my cycling jersey. I cross a wood planked covered bridge spanning the Conestoga river where the land becomes increasingly undeveloped. Fields of green grasses or tilled earth define the quilt of curving terrain. Silos and barns and farmhouses are spaced generously. Amish clothes sway south, between red barns and white houses. Traffic is no concern but occasionally I must pass a horse drawn buggy. The horses leave white hoof marks in the center of the lane and on some roads the buggy wheels have carved depressions in their tracks. Holsteins are everywhere, grazing in the distance or merely feet from my wheels.

Off a thin and lineless country road a few large holsteins are resting in a pasture with a sign beside them reading, “Shady Willow Greenhouse.” Past the OPEN flag I turn into the gravel lane where an amish man and his two little boys are working in a garden. I rest my bike in the gravel and walk into the 20-degrees warmer and nicely humid greenhouse. The cute freckled girl would love this place. I decide that I’ll return her favor by getting her a plant and drop it off tomorrow on my way home.

I place a tiny $2.99 succulent named “freckles” on the counter, where I meet Amanda, the amish girl who runs the greenhouse. Her brother works the same farm but instead milks cows. “How many?” I ask. “About 50 of them.” The farm is simple and by stewarding merely plants and cows, the brother and sister make their living. I’m slightly disappointed to leave the warmth of the vibrant greenhouse and into the brisk world outside. On my left while pedaling out the driveway is a large, seemingly older Holstein laying undisturbed in the paddock.

Cows are commercially milked for five years, through five cycles of giving birth, 9-10 months of milking, and a 2-3 month dry period before starting the cycle over again. As one redditor’s grandmother put it, “a dairy cow is only a dairy cow so long as it keeps producing milk, then it’s a beef cow.” Obviously there’s endless ethical debate to this. Regardless, the Holstein laying on the ground is older than any I’ve seen, and If I had only seen cow comfort until now, this was cow heaven. At the end of the gravel drive three boys play baseball and banter at a typical amish schoolhouse ballfield. Behind them, pneumatic air guns fire in an Amish carpentry shop with new dog houses lining the building.

I suppose that many Amish farms are only as large as they need to support their family. “Grass-based Dairy Farming” reveres the family farm, shunning ideas of agribusiness and ag salesmen that seek to automate and systematize. While the production of say, Kreider’s farm, or even Paul’s, can’t be matched by a fully grass based farm, the quality certainty can, and I believe the cows are happier.

Riding with no sleep in my system feels like riding up a sandy dune in a fog. The gumption and extroversion of yesterday are, well, virtues of yesterday. Today, my softer focus leads me to rest along a roadside pasture in the amish dairy belt. About 14 holsteins stare at me as I stand off the rural road. Through our eyes we communicate. #33 and #34 are most curious of me.

These cows seem more peaceful than I often am and show no signs of distress. Five minutes goes by and we’re still looking at each other. Years ago I read an article saying how red meat was bad for you so I stopped. Then I’d become somewhat sympathetic to those who used exploitation and animal cruelty to further stomp on the animal industry. But looking at #33 and #34, I simply don’t see it here. Yes, cows are put to work, systematically at that, but on Monday so am I. And in the dairy industry there is absolutely no incentive to treat the cows poorly. The farmers who do won’t make it. Paul and farmers like him are careful stewards of their resources and have great respect for their herd. If we all had bosses like Paul we would be well fed and comfortable and ready to do our best work. Exceptions to this are unfortunately too common, but when it’s done well it’s a beautiful thing.

I begin riding south again, spinning around rural bends and waving at amish school boys playing ball, when my mind departs to a lofty place, maybe reaching for the skipped dreams from last night. I see crammed cities and gray cubicles and packed milking parlors and stainless steel contraptions — as both the same. In parallel systems I can’t separate the cow’s duty to provide milk from our duty to provide tax accounting, hazelnut lattes, or brick laying. We’re all milked for something, and oftentimes, even under the best care, it wears on us. And at the end of our days we can escape into our respective pastures. If I’m so inclined I may have fifty more years of production left, and, while more years than the commercial cow, at the end we will both be pulled from production somehow. And all across the county I’ve yet to find a pasture where cows won’t enjoy a moment with me, and through each interaction, a deep appreciation is growing.

DOWN ON THE FARM

Someone who has always held this appreciation is Rose, serving ice cream at “Down on the Farm Creamery”. I find her at the end of a quarter mile lane in a valley between two small ridges, in the creamery building sided with washed pine and roofed with black metal. The farm is like most amish farms — a white house with white vinyl siding and gray asphalt shingles. The barn is red with white trim and the roof is a metallic gray.

I order a waffle cone of chocolate chip cookie dough. Rose tells me her dad once did all the farming and the processing but today the creamery has been so successful he focuses only on processing from raw milk to the final product. “The neighbors bought the cows”, she says, pointing behind her up the hill. “It’s the same cows” she reassures me. The farmer on the hill maintains exactly 55 cows throughout the year and excess cows are usually sold or given to neighbors. In the warm months, as the line extends out the lane, those 55 will supply all the ice cream needed. In the coldest months a portion of the milk is sold elsewhere. Rose’s favorite thing to do on the farm is work in the ice cream shop, or gardening.

For a Wednesday afternoon the typical customers are mom’s with their children, who can crawl around the playground or admire the animals. I sit at a wooden table inside as folks enter and head straight for the fridge storing fresh cheese and milk. I recognize one man who opens the door, a joyful Nigerian man with a contagious laugh who I once met around a friend’s campfire. He’s actually a Christian missionary within Amish communities, of all places. I briefly reintroduce myself and tell him of my travels. Before leaving he encourages me, “God Bless your wonderful adventure!”

After finishing my ice cream I walk over to the curved glass over the freezer housing all the flavors. I stumbled over my words to Rose. “The ice cream is uhhh…”. I pause and my foggy brain fails to find words so I motion my hands like I’m shaking a bowling ball. If my brain was working I would have told her it was the fattest, thickest, butteryest, creamiest ice cream ever.

“… the best ice cream I’ve ever had.” I finished.

Her response is a sweet and humble smile, and, “Thank you.”

It’s impossible to separate the Amish farm from their spiritual roots. Everything flows from it. On the walls of the bathroom are verses for whatever emotional or physical ailments you are feeling in life. On a round table sit pamphlets – ice cream for the soul. Outside, three Amish girls are sitting on the farmhouse’s porch roof, covered in blankets, with books in hand. Moms watch their kids. And little calf, Blackie, trots around his pen. My focus recedes to a trance. Perhaps from the pound of fat in my stomach or that I wanted a nap. But beyond everything I feel the deepest peace. All the afternoon sounds were calming like a mountain stream. Maybe it was the way the Nigerian man said “God bless your wonderful adventure” or Rose’s pride in her work. I don’t know but it was near perfect.

Feeling heavy and sleepy I ride southbound for a few miles until I see a treeline in the distance convincing me I could take a quick nap there. I set up my sleeping mat and sleeping bag along a wooded trail and send a text to my friend who lives near Oxford about getting dinner. In short time I fade away into my own cow comfort.

COWS AND LIFE

I am sitting at the Sawmill restaurant in Oxford, PA with my friend Andrew, my usual bikepacking partner, waiting on a surf and turf cheesesteak and Andrew’s burger. We reminisce old bikepacking trips to northern PA and Vermont where the terrain and demanding miles were plenty to keep us entertained. Andrew knows my eccentricities over thousands of miles and is surprised and delighted by the cow idea. I tell him of all the cows, from Vermont, to the herd in Oklahoma, and remarkably, a story of a few free range cattle in Arizona.

“All day I was riding from the little town of Patagonia in southern Arizona, up to this observatory on top of Mt. Hopkins, like 70 miles round trip on sandy desert backcountry roads. And all day I was so agitated thinking about a conversation with my ex business partner — having imaginary arguments all day long. About six hours into the ride I was coming back to Patagonia, grinding up a loose steep trail, pedalling through my frustrations, when my tire spun out on a patch of stones, stalling me and tipping me over. I was pissed. Just then a group of cattle across the ravine started mooing at me, not nice moos but those ornery, insulting moos. So in the middle of the desert I completely lost it. I cussed them out at the top of my lungs like never before; in new combinations I never knew were possible. In a way it felt amazing to scream so loud with so many profanities, but quickly I felt bad. ‘I’m sorry guys…’ I yelled back. ‘ I’m just having a moment… y’all didn’t do anything… I didn’t mean it.’”

Andrew was losing it at this point, maybe wondering if my current cow trip is more repentance than curiosity. Finally our server delivers our food and I’m excited to replenish from the day’s riding. “I almost prefer,” Andrew says, “keeping rides open, thinking about life and appreciating the freedom of riding bicycles, riding and stopping wherever you want”

“I think it is all that,” I say, chewing on a strip of beef, “You think of everything in life — but now it’s through the lens of cows. And I’ve found that just when you think you are narrowing your focus, the world expands.”

RIVERLANDS OF BULLS AND HILLS

Andrew runs a coffee roasting company out of a small shop near Oxford, where he drops me off to escape the rain coming overnight. The smell of fresh coffee is delightful but even sleeping inside I only manage a few hours of decent sleep.

The morning is met with intense rain so I make a pourover of some Tanzania Peaberry beans. Perfectly framed out the window of the shop are two predominantly white cows along a treeline and a fence. It’s picturesque but by now I’m starting to be done with cows. It won’t rise above sixty degrees today, with intermittent rain, and there’s over 70 miles of hilly terrain to Lebanon where I live. I’ve already seen a lot. What I need to do is get this little plant to Grace. And that is motivation, as my slick tires spray me down with water, heading west towards the abundant steep river hills. A strong tailwind helps.

Being curious of everything cows becomes a matter of disciplined thought, against the desire to stay warm and rush home. As I near the river I begin regretting things I never asked Paul at his farm. If I’m supposed to write about this I should have recorded more senses. Felt the cows. Smelled the air. Heard the rustling of the calves. I begin to grow down on myself as I’m riding up a hill, swaying back and forth with each pedal stroke and holding my eyes on the pavement before me, when a white reflection crosses my periphery in the grass. A minute later the curiosity building from the object finally causes me to turn around, where at once, a clean vessel, a mason jar, filled with what appears to be raw milk, rests along the roadside. Putting the jar up to my face shows an alabaster haze with atmospheric depth, and makes me wonder if this has any ties to naming the “milky way.”

Senses, Nathan… Report with the senses.

I grab the cold metal cap and twist hard before my hand slips, feeling like I’ve scraped my palm on asphalt. Again I try with no budge. Once more and more pain. Finally I think that if I’m going to break this open I need to break the seal, so I crouch down and hoist the jar above my head, eying up the asphalt, and suddenly give it a calibrated whack! The jar explodes across the road and up my leg and all over my red bike! The smell, slightly fowl, begins to emerge, but when I come to think of it I don’t think I know what milk smells like. Now, with some milk still remaining in the busted jar I think about redeeming another sense. Slowly I lift it up to my mouth as potential consequences start flooding my mind. Ehh, I really better not.

With temperatures in the 50s and the morning storm remnants overhead, riding is kept to a brisk tempo. If any reporting is to be done it is brief, like stopping for an Amish boy outside his silo.

“How many cows ya got? I call out.

“Bout thirty,” he replied “got the heifers here.

“What are you doing now?”

“Gotta feed em.”

Or, along a steep river hill before a pen of massive, furry steers, a woman getting her mail warns me of her playful dog who might chase me.

“What does she think about the cattle up here?” I ask.

“Oh, she likes to bark at them — but she would never do anything. She’s scared of them!” She says, “Good luck on those hills!”

If I could make any conclusions along the river it’s that I’m seeing plenty more steer — your angus beef variety — than I am dairy cows.

In Columbia there’s a large historic brick building repurposed for The Turkey Hill Experience, an agritourism museum I also visited in elementary school. Outside of the building stands a 15 foot tall holstein cow statue and above the building is a Turkey Hill Experience water tower that rises far above the town. But today I have no desire to make a reservation. I reason that I may have better luck at the extensive Turkey Hill facility on the rising hill south of Columbia. But there I find no one within the corporate office, and asking a departing trucker what he was hauling left me only feeling stupid. “Ice cream and tea…” he said curtly.

As I reach Columbia, Grace, and the thought of delivering her plant makes me nervous, but it’s mostly sedated by exhaustion. She texts me saying she would be home and that her mom would soon return from the store. Meeting her mom now is just too soon, so I pedal harder on the hills out of Columbia.

Grace’s house is wrapped in a nice porch and sits on a hill. Pedaling up to it is slow and only builds anticipation. Once there she opens the front door wearing a flowy yellow dress with yellow converse. The interaction is brief and sweet. “My mom and I are heading to the Fulton theatre” she tells me.

With my red eyes and my body covered in dirt, sweat, and milk, I give her the tiny succulent. She bursts with joy. The conversation feels like I’m lofted and drifting in the wind, and along the way we secure Saturday’s date — At Fox Meadows Creamery, of course. Grace calls me out for constantly looking at the cars coming up the road, “Are you worried about someone coming up the driveway?” She giggles.

“Maybe a little bit.”

I say goodbye and she tells me to stay safe and to text her when I get home. The parting words carry my exhausted self through the hills out of her neighborhood. The story is complete in my mind, and these miles home are the victory lap, where my mind knows it can rest as my legs softly pedal along.

A couple miles from her house the road rises to offer a long view across the farmlands. Ahead of the view, some fifty yards away, is one lone cow staring at me with her ears perked high and her tail wagging behind her, behind a steel wire fence. The scene begs me to stop and rest. It’s no wonder in my mind that the cow ahead is fully aware of me. And I wonder if behind her steadfast gaze there is anything more going on? Did the cattle in Arizona know of my rage? Did the cows in Vermont know of my peace? I guess I’m in a silly, “are-cows-telepathic?” state of mind. But in my current state nothing stops me from calling out to the cow.

“So, what do you think of her!?”

She maintains her stance and stares back.

“She’s cute, huh!?”

And, whether divine, merely bovine, or somewhere in between, with perfect clouds hanging in the background, she flaps both ears, pauses, stomps her two front hooves, and gives an assertive upward nod. She rests again to look at me, letting out a great exhale, and then yanks her head away, sprinting across the meadow, vanishing at once, over the hillside.

4 responses to “The Cow Story – Biking Lancaster’s Dairy Land and the Quest for Cow Comfort”

You are a priceless chronologicaler of ordinary people and their lives of the ordinary person just like Washington Irving and Charles Kuralt was.You are priceless just as I earlier identified and I urge you to keep it up .Wonderful and magical at the same time.SteveSent from my Verizon, Samsung Galaxy smartphone

LikeLike

Thank you Steve. I’m so grateful for you and your encouraging words. I can still hear you at Timbers saying, “you need to write!” Those words have brought me back to the pen on many occasions. I would give you a hug right now if I could. God bless you Steve.

LikeLike

Just keep being a keen observer and writer of everyday man in everyday situations.It gives the average man a greater appreciation of his ordinary experiences and adds color to his otherwise black and white life.SteveSent from my Verizon, Samsung Galaxy smartphone

LikeLike

Keep it up my friend. You have a gift of writing like people think to themselves because you use the vocabulary of the way people think. Dwight Eisenhower wrote in the same style. I am going to send you a book he wrote called “At Ease…..stories I Tell To Friends.” It’s marvelous.

Steve

LikeLike